By far the most popular blog post I’ve written on this site with more than 6,500 views to date (and counting) was written more than ten years ago, in 2014, on the topic of office configurations that support different forms of sociability. In ‘Figures, doors and passages – revisited. Or: Does your office allow for sociality?‘ I took a classic essay written by architecture scholar Robin Evans (where he compares houses with connected rooms to those with corridors) and then I applied that to the topic of workplace design, thus evaluating four types of possible office configurations. Given the popularity of the post and my continued work in this realm over the last decade, I want to revisit and update the argument with latest research findings, also reflecting on what might have changed due to the changes imposed by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Let’s retrace the original argument briefly (or read the full post and then come back): I summarised Evan’s main proposition that different types of layouts in houses create different affordances for people to meet and interact. Series of connected rooms as built in the Renaissance period, most prominently expressed in Palladian villas for example mean people moving through a space automatically come into close contact with those occupying a room. This corresponds with a society thriving on contact and exchange, called ‘habitual gregariousness’ by Evans. In contrast, the birth of the corridor a few hundred years later meant traffic was removed from rooms which coincided with the societal ideal of being left undisturbed (if one’s privileges afforded it).

It is easy to see how this applies to office buildings and workplace design: the privilege (and status) of the enclosed office as a means of being undisturbed at work, and the common complaints about the noise of the open-plan offices are only two common examples that come to mind. I sketched four office types in a two-by-two matrix (connected versus compartmentalised by open versus enclosed) and then developed two distinguishing criteria for the evaluation of an office building: firstly whether a layout separates movement flows from occupation (i.e., static activities) and secondly, whether a layout concentrates or distributes movement flows.

I want to reflect on this argument, which is amazingly relevant and timely and add three aspects: 1) on the transferability of the argument to other building types and how to measure the sociality potential of a plan, 2) on the question of fit between plan and organisational strategy, and 3) on recent debates on hybrid work in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic and how this might change what we expect from the office in terms of sociality.

Measuring the sociality potential in offices and beyond

While my original post in 2014 only provided sketches of archetypical floorplans and invited readers to reflect on their own offices, a book chapter published in 2018 took these ideas further and applied them to school buildings. The Routledge book ‘Designing Buildings for the Future of Schooling: Contemporary Visions for Education‘ was edited by Hau Ming Tse, Harry Daniels, Andrew Stables and Sarah Cox and in my chapter entitled ‘Corridors, classrooms, classification – The impact of school layout on pedagogy and social behaviours‘, I framed school buildings as pedagogical tools and argued that the corridor structures of schools are much overlooked, yet highly influential in shaping social interactions among students, which in turn contribute to pedagogical principles.

I used exactly the same two criteria outlined in my 2014 blog post, i.e., 1) What is the degree of choice for movement? and 2) What is the degree of overlap between movement and occupation? For each question I considered how strongly or weakly the system was classified, that means how strongly or weakly boundaries were maintained. Where lots of alternative movement choices existed, the space was considered weakly classified. Likewise, where movement and occupation were in close and frequent exchange, a weak classification was assumed. Based on this idea of classification (borrowed from educational scholar Basil Bernstein), I then developed modelling methods built on the theory of space syntax to compare and contrast five different contemporary school buildings in the UK and Denmark, and evaluate them according to the strength of their classification systems and what this might mean for social life: Chelsea Academy (UK), the Kingsdale Foundation School (UK), the UCL Academy (UK), Ørestad Gymnasium (Denmark) and Hellerup School (Denmark).

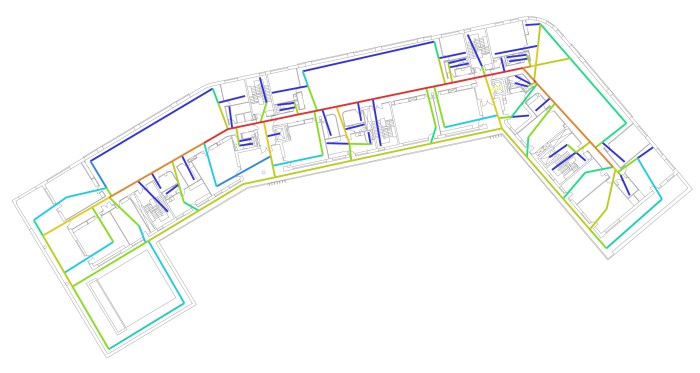

The below floor plan shows how corridors systems were classified using UCL Academy as an example. With a central corridor (shown in red, signifying the highest choice of movement, if all paths from all segments to everywhere else are modelled) and a secondary movement route alongside outdoor terraces (shown in yellow), as well as lots of loops in the local movement system, this was an example of a rather weakly classified system, offering lots of choice for movement. At the same time, some of the movement paths lead directly through teaching spaces (the so called ‘superstudios’), while the outdoor corridor at least offers visual glimpses into teaching spaces, hence this school was considered to offer moderate overlap of movement and occupation.

Segment line model of UCL Academy showing parts of the corridors with high choice in red and low choice in blue

The comparative analysis provided in the book chapter allows for a nuanced and detailed assessment of the potential for sociality as afforded by the school plans beyond the categorical labels of a school as ‘open’, ‘enclosed’, ‘connected’ or ‘compartmentalised’.

This method of analysing main circulation paths and what is experienced alongside them can obviously be applied back to workplace environments and contribute to an appreciation of the many different forms of organising space within the wide spectrum between the two poles of total openness and total enclosure.

Fit between plan and organisational strategy

This leads nicely to my second point of fit between spatial and organisational structures. The hotly led debate around open-plan offices of the 2010s and their apparent unsuitability for knowledge work (as for example evident in my all-time favourite headline on open-plan offices as ‘devised by satan in the deepest caverns of hell‘) in my view obfuscates the real issues we need to tackle: is a workplace design helping people achieve what they need to achieve, or in other words, does the office layout fit with the strategies, cultures, mission and vision of an organisation? Open-plan offices might be good for some types of knowledge work and certain kinds of workflows (think trading floors of banks where information needs to travel at speed), whereas they might be terrible choices for other types of knowledge work (such as academic work which requires solitude and concentration, or confidentiality when engaged in pastoral care for students). Yet, the debate around offices is mostly led by categorical labels (open-plan, hotdesking etc.), ignoring detailed design choices, for example, how open is open, how large is the floor plate, how many people (and who) am I surrounded by and so on.

Building on my 2014 sociability blog post, which raises an important question but admittedly sticks to categorical evaluations of open or closed, and another blog post from 2014 which outlines the main gist of the idea that open-plan is not always from hell, I have published two papers on workplace design in the meantime that discuss design choices in more depth and develop criteria by which to judge them.

In the 2021 PLOS ONE paper ‘Differential perceptions of teamwork, focused work and perceived productivity as an effect of desk characteristics within a workplace layout‘ (I know, I know, that’s a handful of a title), I explored together with my co-authors Petros Koutsolampros and Rosica Pachilova what difference it made to someone’s satisfaction at work where exactly in the open-plan office they sat. In other words, we looked at what the best seat in the office might be, and it turns out that desks in areas with fewer other desks around them in direct visibility (so smaller open-plan areas) and those desks facing the room were preferable. This allows us to appreciate nuances in workplace design in relation to people’s perceptions of productivity and workflow, which is an important part of organisational strategy (or at least should be).

The question of fit was directly addressed in another paper of mine, also published in 2021 in the Journal of Managerial Psychology, this time with co-author Matt Thomas and entitled ‘Socio-spatial perspectives on open-plan versus cellular offices‘. There, we frame the debate on open-plan versus enclosed office structures as a question of fit between the demands placed on an organisation and what it therefore values, and the structures of the interior workplace layout and whether it supports the organisation. We applied a metric that measured the degree of correspondence or non-correspondence for each office, i.e., to which degree different work groups were brought into close spatial proximity in their everyday practices, as expressed in the seating plan and as measured by movement to and from main attractors such as the coffee machine, meeting rooms, the entrance / exit, etc. If members of staff had the potential to meet as many colleagues from other work groups / teams while moving through the space as of their own group, this was called a non-correspondent system, and expressed by a value near zero on a scale from -1 to +1 based on a mathematical formula called Yule’s Q (for details please see the paper, where this is explained in depth).

Here’s an example from one of our case studies, a research institute in Germany, where enclosed offices (see plan below) are allocated in an almost random looking manner to researchers belonging to different research groups. This non-correspondent system, where people frequently meet others from different teams suits the demands placed on the organisation (need for innovation and generation of new research insights and breakthrough findings) but – interestingly – does not fit the standard narrative that enclosed offices are detrimental to innovation and frequent random encounters. Similarly, the other two cases we studied showed high levels of fit between demands placed on them and the layout structures. We therefore conclude that “neither office form automatically guarantees superiority. Cellular offices can work and so can open-plan layouts.”

Floor plan of the institute with offices coloured according to research group

This line of work builds on the idea of sociality in the office as a result of office layouts and proposes ways in which the potential embedded in the layout can be better understood, measured and evaluated.

Hybrid work: what does this mean for the sociality of the office?

Finally, I want to briefly reflect on the changes to workplaces that we experienced in the last five years as a result of the global Covid-19 pandemic. Throughout those five years, demands on offices and ideas of desired sociality have shifted and changed dramatically. When Covid-19 first hit us in 2020 and many offices around the world had to close for months on end, sociality was reduced to videocalls. At this time I wrote an opinion piece in the Guardian calling for a reimagination of the office as a place of togetherness. A paper published in 2021 in the Corporate Real Estate Journal picked up this thread and warned of a potential ‘Innovation deficit‘ in coming years, as lockdowns and working from home might have shrunk people’s networks at work. And then in 2023, I published a paper in the journal Buildings & Cities outlining challenges of hybrid work including calls for offices to act as social hubs rather than providing a sea of desks.

So, what can we take away from these contributions for the new demands placed on offices regarding sociality? Maybe this: that offices continue to be needed, unless organisations build strong cultures of collaboration and sociality on digital platforms; that organisations following a hybrid work model (which is the majority) need to rethink in what ways their office can support sociality and the bringing together of people (as that’s the main reason for people to face the commute); and that with all demands for sociality, we shouldn’t forget that the office also needs to act as a place for solitude, quiet and concentrated work, for example by those with insufficient space to work from home.

It seems that we need nuance and balance more than ever.

References cited:

Sailer, K. (2019). Corridors, Classrooms, Classification. The impact of school layout on pedagogy and social behaviours. In H. M. Tse, H. Daniels, A. Stables, & S. Cox (Eds.), Designing Buildings for the Future of Schooling (pp. 87-112). London and New York: Routledge.

Sailer, K. (2020, 04 Aug). Covid will force us to reimagine the office. Let’s get it right this time. The Guardian.

Sailer, K., Koutsolampros, P., & Pachilova, R. (2021). Differential perceptions of teamwork, focused work and perceived productivity as an effect of desk characteristics within a workplace layout. PLoS ONE, 16(4), e0250058.

Sailer, K., & Thomas, M. (2021). Socio-spatial perspectives on open-plan versus cellular offices. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 36(4), 382-399.

Sailer, K., Thomas, M., & Pachilova, R. (2023). The challenges of hybrid work: an architectural sociology perspective. Buildings & Cities, 4(1), 650-668.

Sailer, K., Thomas, M., Pomeroy, R., & Pachilova, R. (2021). The Innovation Deficit: The importance of the physical office post COVID-19. Corporate Real Estate Journal, 11(1), 79-92.